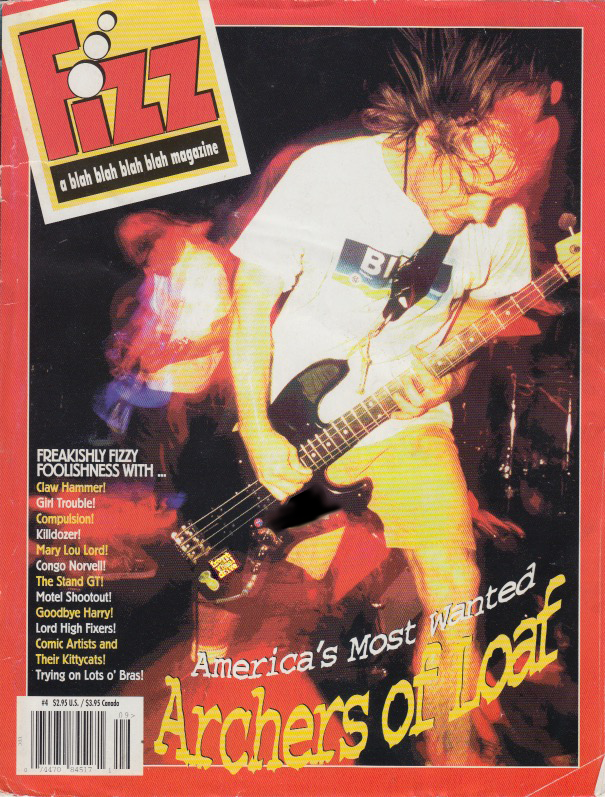

A few years ago, I was having lunch at a bar in Chicago when an Archers of Loaf song came on over the speakers. Excited, I told my partner what a big fan I am, about the first time I saw them at the Crocodile Café in Seattle, and that I saw them a dozen or so times during their first run in the 1990s, once even traveling up to Vancouver to see them play with Treepeople and Spoon. I told her how, fancying myself an indie-rock mogul, I had plans to put together a compilation of Chapel Hill bands, and they were the first to agree to contribute a song. And how I’d gotten to be pretty good friends with their bass player, Matt Gentling, how he’s also a rock climber, and we’ve stayed in touch over the years.

As we continued to eat, song after song of theirs came on. Now, as great as they are, the Archers are not a normal thing to hear in public, much less several of their songs in a row. I finally went up to the bar and asked who the Archers of Loaf fan was. No one knew what I was talking about. I explained the same thing I just explained to you, that hearing that many of their songs in a row wasn’t normal. The third person I asked said it was just a streaming service. Somehow the streaming service’s algorithm had gotten stuck on the Archers of Loaf catalog. Not a bad place to get stuck, as far as my lunch was concerned, but it still irked me that I was alone in the experience I was having.

Studies of the digital sharing of music call it “playlistism,” a subcultural ritual that reinforces the links between music and collective identity through the practice of sharing playlists. Assuming that we compile playlists to represent our identities, the sharing of them should show how we present ourselves through music. We didn’t use the old P2P networks to share in this traditional sense. In this way, playlists are more akin to analog mix tapes. We are what we like. In any form, when compiling and sharing our musical tastes, we go from saying, “I like this” to “I’m like this.” In the example above, there’s no one saying anything. Human agency is absent.

Music fans of a certain age belabor the pre-internet era, extolling the effort it took not only to find the good stuff but also to find out about it in the first place. We relied heavily on regionally curated spaces that are less and less influential now, where they exist at all. Local record stores, small weekly papers and zines, indie labels, narrowly focused radio shows, and tiny venues created community and shared knowledge. I do not lament the effort it took to find new music then, but the missed connections like my Archers of Loaf lunch don’t happen when you’re truly sharing an experience. It’s a loss that doesn’t matter to generations since because they never had it to lose. However, it’s one thing to be cut off from each other by choice. It’s entirely another when we don’t even choose it.

The sound that 1990s Seattle is known for seems to be the last historical exemplar that emerged from such a community, formed unfettered or influenced by outside forces. For example, the movement’s flagship label, Sub Pop, started as a zine, a compilation cassette series, and a column in The Rocket, one of Seattle’s local music papers. It was a special time and a special place. Not only did all of this happen in the time untainted by the internet, but the Pacific Northwest is also isolated geographically from the paths of nationally touring bands. I moved to Seattle in the summer of 1993, after the world knew about what was going on in the area, but before it peaked. When it was still what William Gibson would call a bohemia. As he told WIRED in 1995, “I think bohemians are the subconscious of industrial society. Bohemians are like industrial society, dreaming.” He continues:

Punk was the last viable bohemia that we’ve seen, perhaps the last bohemian movement of all time. I’m afraid that bohemians will eventually come to be seen as a byproduct of the industrial civilization; and if we’re in fact at the end of industrial civilization, there may be no more bohemians. That’s scary. It’s possible that commercialization has become so sophisticated that it’s no longer possible to do that bohemian thing.

I put this question to Malcolm Gladwell years ago, who wrote about youth culture’s commodification in his bestselling 2001 book The Tipping Point, and he responded, “Teens are so naturally and beautifully social and so curious and inventive and independent that I don’t think even the most pervasive marketing culture on earth could ever co-opt them.” Gibson is not so optimistic, or he wasn’t in 1995. Here he talks about Seattle’s music scene, which by that time had had a very public and much-debated commercial co-opting:

Look what they did to those poor kids in Seattle! It took our culture literally three weeks to go from a bunch of kids playing in a basement club to the thing that’s on the Paris runways. At least, with punk, it took a year and a half. And I’m sad to see the phenomenon disappear.

Perhaps this says more about where Gibson’s head was at the time than it does about the creativity of the youth. After all, we’ve seen plenty of cool things happen since 1995, and Gibson was writing Idoru (1996), one of his darker visions of modern culture, saturated with multi-channel, tabloid television and the rampant collecting of purchase data by unscrupulous marketers. Focus groups, surveys, and other ethnographical cool-hunting techniques farm information about users. At best, they seek to find out how people are using products, how they perceive brands, and what their desires are in order to market to and design for them better. At worst, they can seem invasive and downright icky, but they are where our wants wander into the manufactured world.

As these contexts collapse, we lose control of the processes, and we sometimes lose ourselves altogether. Thanks to some anonymous algorithm, I got to hear Archers of Loaf songs for a whole lunch hour one day. Maybe one of them was able to buy lunch themselves.